Feeling Rested Is Not the Same as Sleeping Longer

Many people assume that feeling rested is simply a matter of sleeping more hours. In reality, the sensation of being refreshed after sleep is determined by how sleep is structured and regulated, not just by its duration.

Sleep is a complex biological process governed by interacting systems that control timing, depth, continuity, and recovery. When these systems align, people wake up feeling mentally clear, physically restored, and emotionally stable. When they do not, sleep may be long but unrefreshing.

Understanding the science behind feeling rested requires looking beyond the clock.

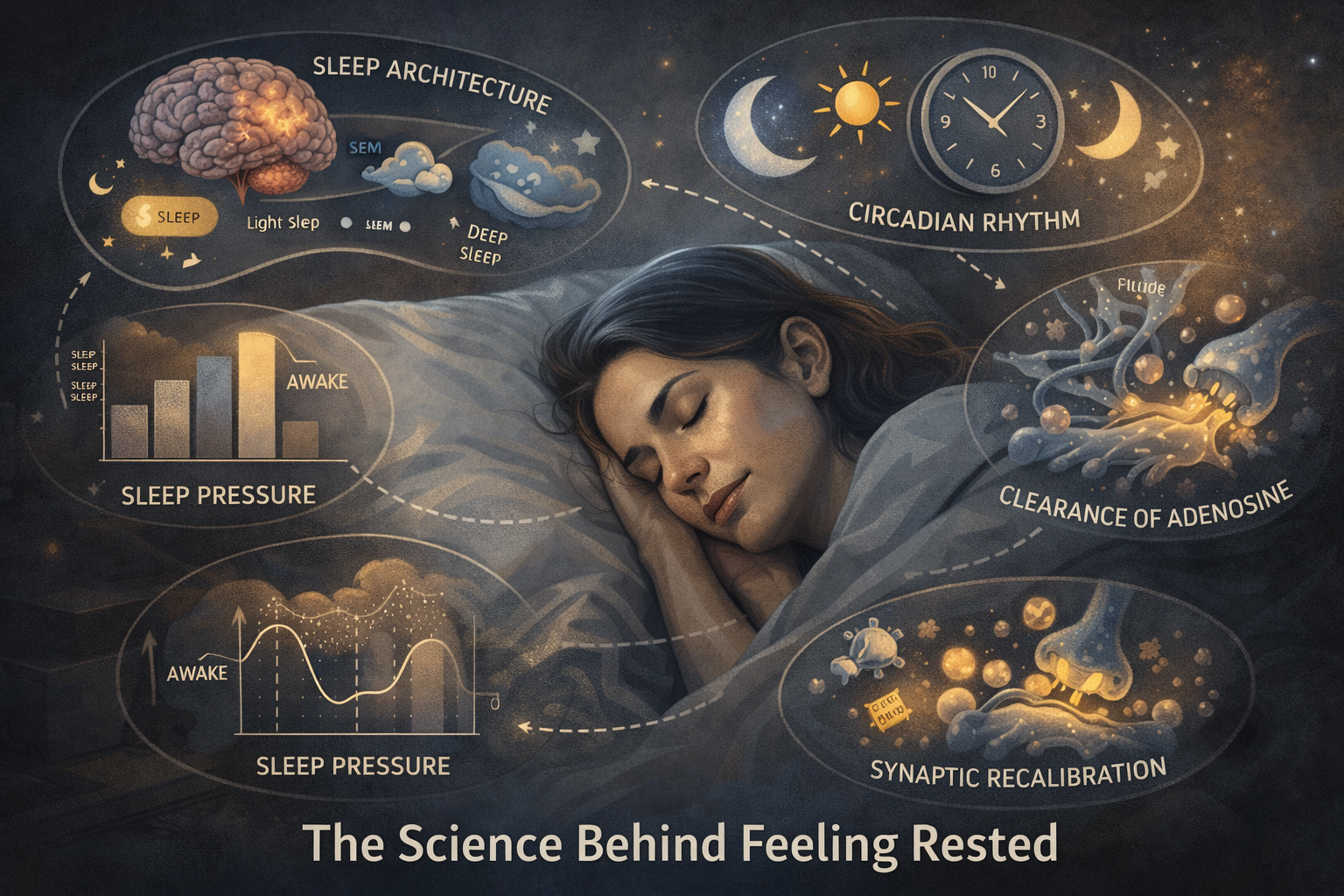

The Role of Sleep Architecture

Sleep is organized into repeating cycles, each composed of different stages, including light sleep, deep sleep, and REM sleep. This structure is known as sleep architecture.

A typical night includes four to six cycles, each lasting about 90 minutes. Feeling rested depends on:

-

Sufficient deep sleep early in the night

-

Adequate REM sleep in later cycles

-

Smooth transitions between stages

-

Minimal fragmentation or awakenings

Deep sleep supports physical recovery, metabolic regulation, and immune function. REM sleep plays a central role in emotional processing, learning, and memory integration. Disruption of either stage can significantly reduce perceived restfulness, even if total sleep time appears adequate.

Sleep Pressure and Homeostatic Balance

Another key factor behind feeling rested is sleep pressure, a biological drive that builds during wakefulness and dissipates during sleep.

The longer a person stays awake, the stronger the pressure to sleep becomes. High-quality sleep efficiently reduces this pressure. Poor-quality or fragmented sleep does not.

When sleep pressure is not adequately relieved, individuals may wake up feeling:

-

Heavy or mentally foggy

-

Physically sluggish

-

Unmotivated or irritable

This explains why sleeping longer does not always improve how rested someone feels. The issue is not the amount of sleep, but how effectively sleep reduces accumulated pressure.

Circadian Rhythm Alignment

The circadian rhythm is the internal biological clock that regulates sleep timing, hormone release, body temperature, and alertness. Feeling rested strongly depends on sleeping in alignment with this rhythm.

When sleep occurs at biologically appropriate times:

-

Sleep stages organize more efficiently

-

Hormonal recovery processes function optimally

-

Morning alertness improves

Circadian misalignment—such as irregular bedtimes, late-night light exposure, or social jet lag—can reduce sleep quality even when total sleep duration remains unchanged.

People who sleep “enough” hours but at inconsistent times often report waking unrefreshed because their internal clock and sleep schedule are out of sync.

The Importance of Sleep Continuity

Sleep continuity refers to how uninterrupted sleep remains throughout the night. Frequent micro-awakenings, even if not remembered, fragment sleep architecture and reduce its restorative value.

Causes of reduced continuity include:

-

Stress and cognitive hyperarousal

-

Environmental noise or light

-

Sleep-disordered breathing

-

Irregular sleep schedules

Fragmented sleep limits time spent in deeper stages and prevents smooth progression through cycles. As a result, the brain and body fail to complete key recovery processes, leading to persistent fatigue despite adequate time in bed.

Neurochemical Recovery During Sleep

Feeling rested is also tied to neurochemical balance.

During sleep, especially deep sleep, the brain reduces levels of neuromodulators associated with wakefulness, such as norepinephrine and cortisol. This downregulation allows neural circuits to reset sensitivity and restore efficiency.

At the same time, sleep supports:

-

Synaptic recalibration

-

Energy restoration at the cellular level

-

Clearance of metabolic byproducts

If sleep is shallow or repeatedly interrupted, these neurochemical processes remain incomplete, contributing to the sensation of mental exhaustion upon waking.

Why Subjective Rest Does Not Always Match Objective Sleep

Interestingly, how rested someone feels does not always correlate perfectly with measured sleep duration. This disconnect occurs because subjective restfulness reflects integrated recovery, not isolated metrics.

Two individuals may both sleep seven hours, yet experience very different outcomes depending on:

-

Sleep timing

-

Sleep depth distribution

-

Fragmentation

-

Stress levels

This is why wearable data alone cannot fully explain why someone feels rested or not. Biological context matters more than raw numbers.

The Accumulation Effect of Chronic Disruption

When sleep architecture, circadian alignment, and continuity are repeatedly disrupted, the feeling of being rested gradually disappears. Over time, the nervous system adapts to chronic sleep strain, lowering baseline alertness and recovery capacity.

This adaptation can make fatigue feel “normal,” masking the extent of underlying sleep debt. Restfulness only returns when sleep quality is consistently restored, not through occasional recovery nights.

The Key Takeaway

Feeling rested is not the result of a single factor. It emerges when sleep architecture, sleep pressure, circadian timing, and continuity work together.

More sleep does not automatically mean better recovery. High-quality, well-timed, and uninterrupted sleep is what allows the brain and body to complete the processes that produce true rest.

Understanding this distinction is essential for addressing persistent fatigue and restoring long-term sleep health.