How insufficient sleep alters brain function, perception, and emotional control

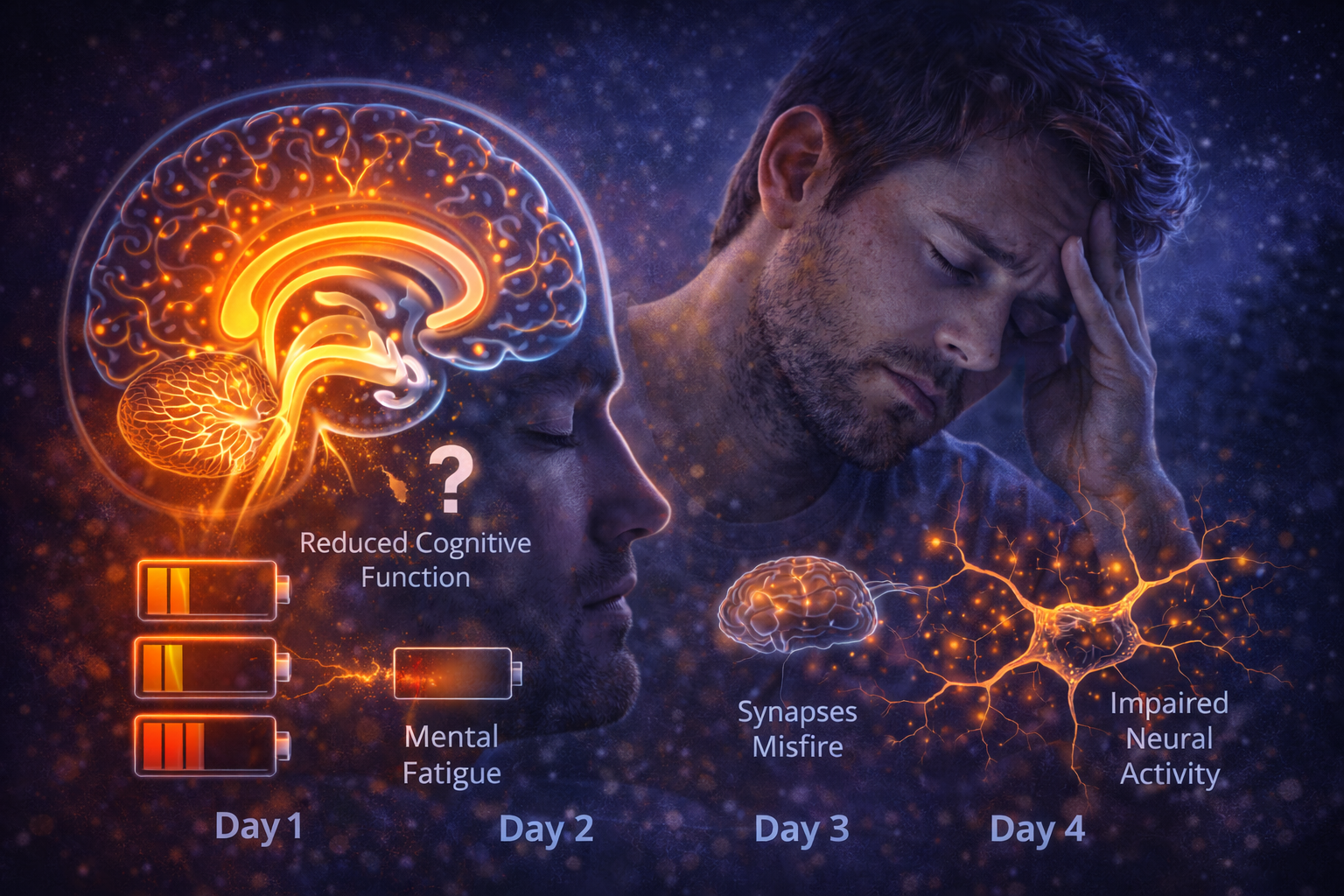

Lack of sleep is often described as feeling tired or unfocused, but the real effects go much deeper. When you don’t sleep enough, the brain does not simply run on less energy — it begins to operate differently.

Even short periods of insufficient sleep change how the brain processes information, regulates emotions, and evaluates risk. These changes are biological, predictable, and cumulative, affecting performance long before severe exhaustion is obvious.

Sleep Is Active Brain Maintenance

Sleep is not a shutdown state for the brain.

During sleep, neural networks reorganize, synaptic connections are recalibrated, metabolic waste is cleared, and memory is consolidated. These processes are essential for maintaining efficient brain function.

When sleep is shortened or disrupted, this maintenance is incomplete. The brain remains functional, but with reduced efficiency and increased strain.

Attention and Focus Decline First

One of the earliest effects of insufficient sleep is impaired attention.

The brain struggles to sustain focus, especially on tasks that require continuous concentration. Reaction times slow, and brief lapses of attention become more frequent.

These micro-failures often go unnoticed, but they significantly increase error rates and reduce overall cognitive reliability.

Memory Formation Becomes Less Efficient

Sleep plays a crucial role in memory consolidation.

Without enough sleep, the brain struggles to stabilize new information. Learning becomes slower, recall less reliable, and mental clarity reduced.

This effect is not limited to complex tasks — even simple information processing suffers when sleep is insufficient.

Decision-Making and Judgment Are Altered

Sleep deprivation changes how the brain evaluates choices.

Risk assessment becomes distorted, impulse control weakens, and long-term consequences carry less weight. The brain favors immediate rewards over thoughtful decisions.

This shift explains why people make poorer choices when sleep-deprived, even while believing they are thinking clearly.

Emotional Regulation Breaks Down

The emotional centers of the brain are highly sensitive to sleep loss.

When sleep is insufficient, emotional responses become stronger and less regulated. Irritability increases, stress tolerance decreases, and negative emotions are amplified.

At the same time, the brain’s ability to moderate these reactions weakens, creating emotional volatility.

The Brain’s Error Detection System Weakens

Sleep-deprived brains are less aware of their own mistakes.

As performance declines, the brain’s ability to monitor errors also deteriorates. This creates a dangerous gap between perceived and actual functioning.

People often feel “functional” while objectively performing far below baseline.

Neural Communication Becomes Less Efficient

Insufficient sleep disrupts communication between brain regions.

Signals travel more slowly, coordination weakens, and cognitive processes require more effort. Tasks that once felt automatic become mentally taxing.

This inefficiency contributes to the heavy, foggy feeling commonly associated with sleep loss.

Why the Brain Feels Foggy

Brain fog is not a vague sensation — it reflects real neural changes.

Reduced sleep impairs waste clearance, disrupts synaptic balance, and weakens network coordination. The result is slowed thinking, reduced clarity, and mental heaviness.

This fog often persists even after brief recovery sleep.

Cumulative Effects Over Time

One night of poor sleep is manageable. Repeated nights are not.

As insufficient sleep accumulates, deficits compound. Cognitive performance declines progressively, emotional regulation worsens, and resilience erodes.

The brain does not fully reset between nights unless sleep becomes consistent and sufficient.

Why Willpower Can’t Override These Changes

Motivation does not restore neural function.

While effort can temporarily mask symptoms, it cannot replace the biological processes that occur during sleep. The brain requires sleep to maintain itself, regardless of discipline or intention.

Ignoring this requirement leads to predictable degradation.

The Core Idea to Remember

When you don’t sleep enough, your brain does not simply feel tired — it changes how it operates.

Attention, memory, decision-making, emotional control, and self-awareness all decline. These effects accumulate quietly, often before you realize how impaired you are.

Sleep is not optional for the brain. It is the process that keeps thinking clear, emotions stable, and perception accurate.