How stress, timing, and overstimulation keep the brain alert when it should shut down

Feeling exhausted yet unable to fall asleep is one of the most frustrating sleep experiences. The body feels depleted, but the mind remains alert, restless, and active. Thoughts race, tension lingers, and sleep feels just out of reach.

This “wired but tired” state is not a contradiction. It reflects a mismatch between physical fatigue and neurological alertness. The problem is not a lack of tiredness — it is that the brain has not received the right signals to disengage.

Physical Fatigue and Mental Arousal Are Different Systems

Feeling tired does not automatically mean the brain is ready for sleep.

Physical fatigue reflects energy depletion in muscles and body systems. Mental arousal reflects brain activity, stress signaling, and alertness regulation. These two systems can move in opposite directions.

At night, it is possible for the body to be exhausted while the brain remains activated, especially under conditions of stress or circadian disruption.

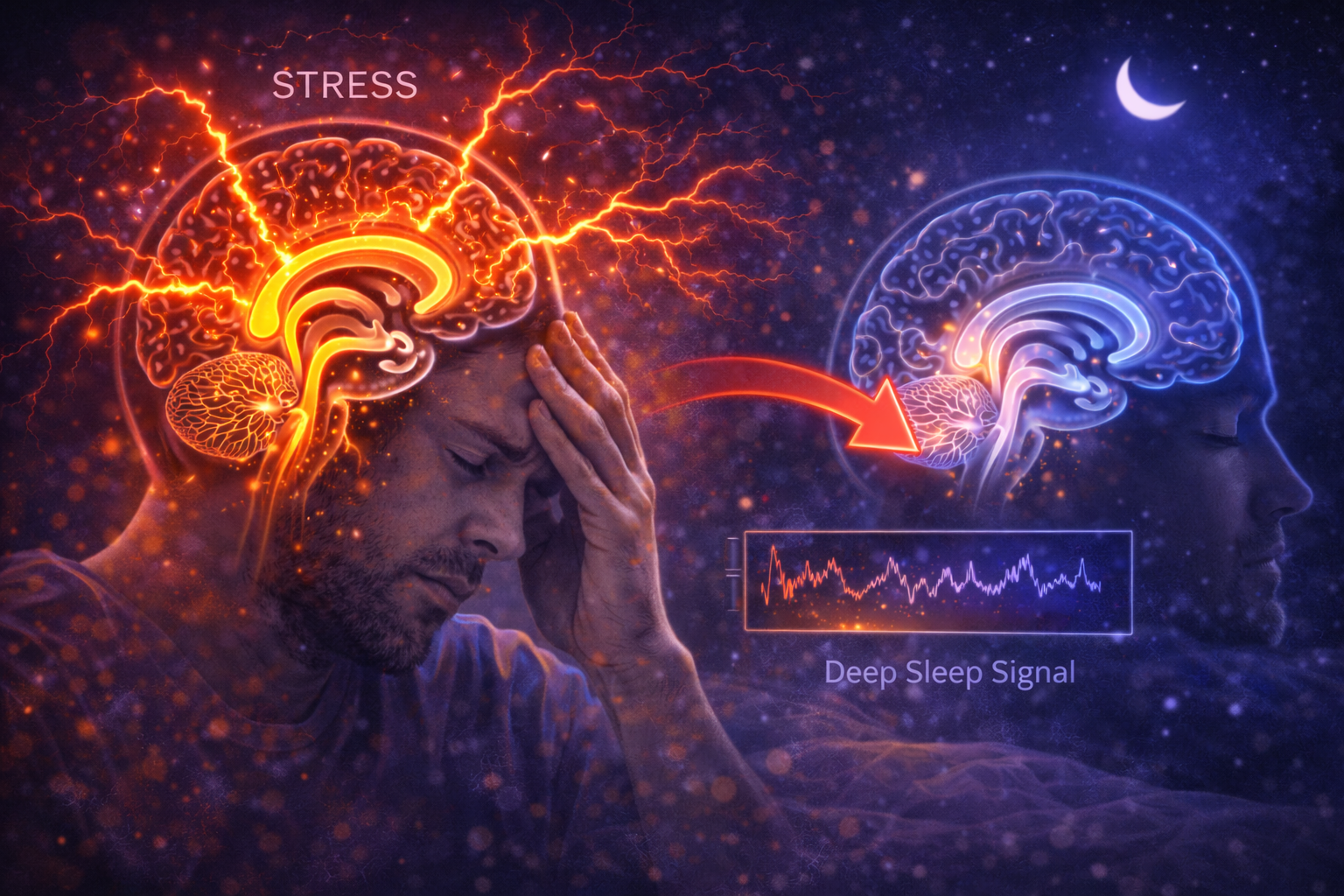

The Role of the Stress Response

One of the main drivers of feeling wired at night is stress-related arousal.

Stress hormones such as cortisol increase alertness and vigilance. When stress is prolonged — even psychological or low-grade stress — these hormones may remain elevated into the evening.

This keeps the brain in a problem-solving, threat-monitoring mode that conflicts with sleep onset, even when the body needs rest.

Why the Brain Struggles to Power Down

Sleep requires a gradual reduction in neural activity.

When the brain remains stimulated — by worry, planning, emotional processing, or mental load — it resists this transition. Thoughts continue to loop, attention remains externally or internally engaged, and sleep pressure is overridden by alertness.

The result is lying in bed feeling mentally “on” despite physical exhaustion.

Circadian Timing and Evening Alertness

Circadian timing plays a critical role in nighttime alertness.

For later chronotypes, biological alertness naturally peaks later in the evening. When combined with stress or stimulation, this peak can feel exaggerated, producing a wired sensation at night.

In this case, tiredness reflects accumulated fatigue, while alertness reflects circadian and stress-driven activation.

Overstimulation and Modern Evenings

Modern evenings are rarely quiet for the brain.

Screens, artificial light, information overload, and constant cognitive engagement keep alertness elevated. Even passive scrolling provides novelty and emotional input that the brain treats as stimulation.

This environment delays the natural decline in alertness and reinforces the wired-but-tired state.

Why Forcing Sleep Makes It Worse

Trying to force sleep often backfires.

When sleep does not arrive easily, frustration increases. This emotional response further activates stress systems, raising alertness even more.

The brain interprets effort as a signal to stay awake, creating a feedback loop where trying harder to sleep increases wakefulness.

Sleep Pressure Isn’t Always Enough

Sleep pressure builds the longer you are awake.

However, high sleep pressure alone does not guarantee sleep if alertness remains elevated. The brain prioritizes perceived threat or stimulation over rest.

This explains why extreme tiredness does not always lead to immediate sleep when the brain is still “on.”

Why This Pattern Repeats Night After Night

The wired-but-tired state often becomes habitual.

When nights repeatedly involve mental activation in bed, the brain learns to associate bedtime with alertness. This conditioning makes future nights more difficult, even when stress levels improve.

The pattern is maintained by timing, stimulation, and learned arousal.

Reducing Nighttime Arousal

Breaking the cycle requires reducing arousal, not increasing effort.

Supporting circadian alignment, reducing evening stimulation, and allowing alertness to decline gradually help the brain disengage. The goal is not to force sleep, but to remove the signals that prevent it.

When alertness falls naturally, sleep follows.

The Core Idea to Remember

Feeling wired but tired at night means the brain is still activated despite physical fatigue.

Stress, overstimulation, and circadian timing keep alertness high when it should be declining. Sleep does not arrive because the brain has not received permission to shut down.

Sleep becomes easier when alertness is allowed to fade — not when tiredness is pushed harder.