Why the “right” bedtime depends on internal timing, not fixed clock hours

People often ask what time they should go to bed, expecting a precise answer like 10:00 p.m. or 11:00 p.m. Bedtime advice is frequently presented as a universal rule, disconnected from individual biology.

In reality, the best time to go to bed is not defined by the clock alone. It is determined by biological timing — specifically, how your circadian rhythm, sleep pressure, and chronotype interact. When bedtime aligns with these internal processes, sleep feels easier and more restorative. When it does not, sleep becomes forced and fragmented.

Why There Is No Universal Bedtime

Human sleep timing varies widely.

Some people feel naturally sleepy early in the evening, while others remain alert well into the night. These differences are not habits or preferences; they reflect biological variation in circadian timing.

A bedtime that works perfectly for one person may be biologically inappropriate for another. This is why rigid bedtime rules often fail, even when followed consistently.

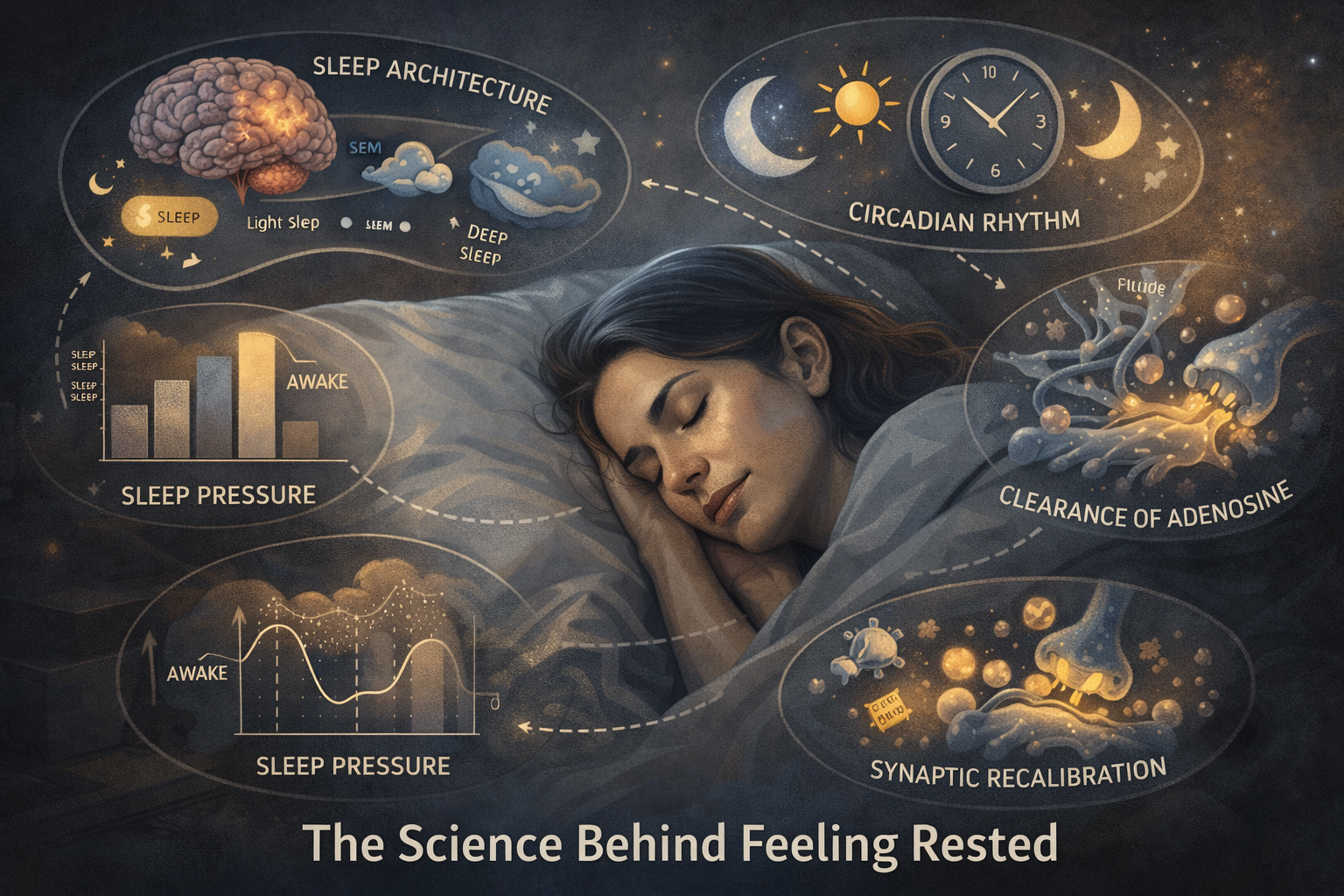

The Role of the Circadian Rhythm in Bedtime

The circadian rhythm regulates when the brain transitions from alertness to readiness for sleep.

As evening approaches, alertness gradually declines, body temperature begins to drop, and hormonal signals shift toward rest. This process unfolds on a schedule determined by the internal clock, not by social expectations.

The optimal bedtime occurs when this biological transition is already underway. Going to bed too early or too late disrupts this process, making sleep harder to initiate and less efficient.

Sleep Pressure and Its Interaction With Timing

Sleep pressure builds the longer you stay awake.

This pressure works together with the circadian rhythm to determine when sleep feels natural. When both systems align — sufficient sleep pressure and appropriate circadian timing — sleep onset is smooth.

If sleep pressure is high but circadian timing is misaligned, falling asleep can still be difficult. This explains why extreme fatigue does not always guarantee easy sleep.

How Chronotype Influences Ideal Bedtime

Chronotype plays a major role in determining when bedtime feels right.

Earlier chronotypes experience the biological transition to sleep earlier in the evening, while later chronotypes reach this transition much later. Forcing an early bedtime on a later chronotype often results in prolonged sleep onset and restless nights.

Understanding chronotype helps explain why advice about early bedtimes works for some people and consistently fails for others.

Why Going to Bed Too Early Backfires

Going to bed before the brain is biologically ready can increase alertness rather than reduce it.

When bedtime is imposed too early, sleep pressure may not be sufficient, and circadian signals may still promote wakefulness. The result is lying awake, increased frustration, and heightened cognitive activity.

Over time, this pattern can condition the brain to associate bedtime with wakefulness instead of rest.

Why Going to Bed Too Late Has Consequences

Delaying bedtime beyond the biological window also carries costs.

Staying awake past the natural sleep onset period often reduces sleep quality and shortens total sleep time. Late bedtimes can interfere with deep sleep distribution and increase morning grogginess, especially when wake-up times are fixed.

Chronic late bedtimes also shift circadian timing further, making it progressively harder to fall asleep earlier in the future.

How Modern Life Disrupts Biological Bedtime

Artificial lighting, screens, and irregular schedules interfere with the brain’s ability to recognize nighttime.

Even when biological readiness for sleep emerges, bright light and mental stimulation can delay the transition. This creates a gap between internal signals and actual bedtime, weakening sleep quality.

Modern environments often encourage later bedtimes without adjusting wake-up times, amplifying circadian misalignment.

Finding the Right Bedtime for Your Biology

The best bedtime is one that aligns with both sleep pressure and circadian timing.

Rather than focusing on a specific hour, observing patterns is more effective. When sleep onset feels easy and consistent, timing is likely aligned. When sleep feels forced or delayed, timing may be off.

Biological bedtime often reveals itself through repeated cues, not through rigid rules.

Why Consistency Matters More Than the Exact Hour

Once a biologically appropriate bedtime is found, consistency becomes critical.

Regular sleep timing strengthens circadian alignment and improves sleep efficiency. Small variations are tolerable, but frequent large shifts confuse the internal clock and reduce sleep quality.

The brain values predictability more than precision.

The Core Idea to Remember

The best time to go to bed is not a fixed hour on the clock. It is the moment when biology signals readiness for sleep.

When bedtime aligns with circadian timing, sleep feels natural and restorative. When it does not, effort increases and quality declines.

Understanding bedtime through biology rather than rules allows sleep to become easier, deeper, and more reliable over time.