Why excessive or poorly timed sleep can leave you feeling drained instead of restored

Sleep is usually seen as the cure for fatigue. When energy drops, the natural response is to sleep longer, stay in bed more, or “catch up” on rest. Yet many people discover an uncomfortable paradox: after sleeping a lot, they feel heavier, foggier, and less motivated.

This does not mean sleep is harmful. It means that more sleep is not always better sleep. When sleep duration exceeds what the brain can use efficiently — or when it occurs at the wrong time — it can actually worsen how rested you feel.

Sleep Restores Through Quality, Not Quantity

Sleep works through efficiency, not accumulation.

The brain restores itself during specific sleep stages that occur at biologically appropriate times. Once those processes are completed, additional time in bed adds little benefit.

When sleep extends beyond the optimal window, recovery does not increase proportionally. Instead, sleep quality can decline.

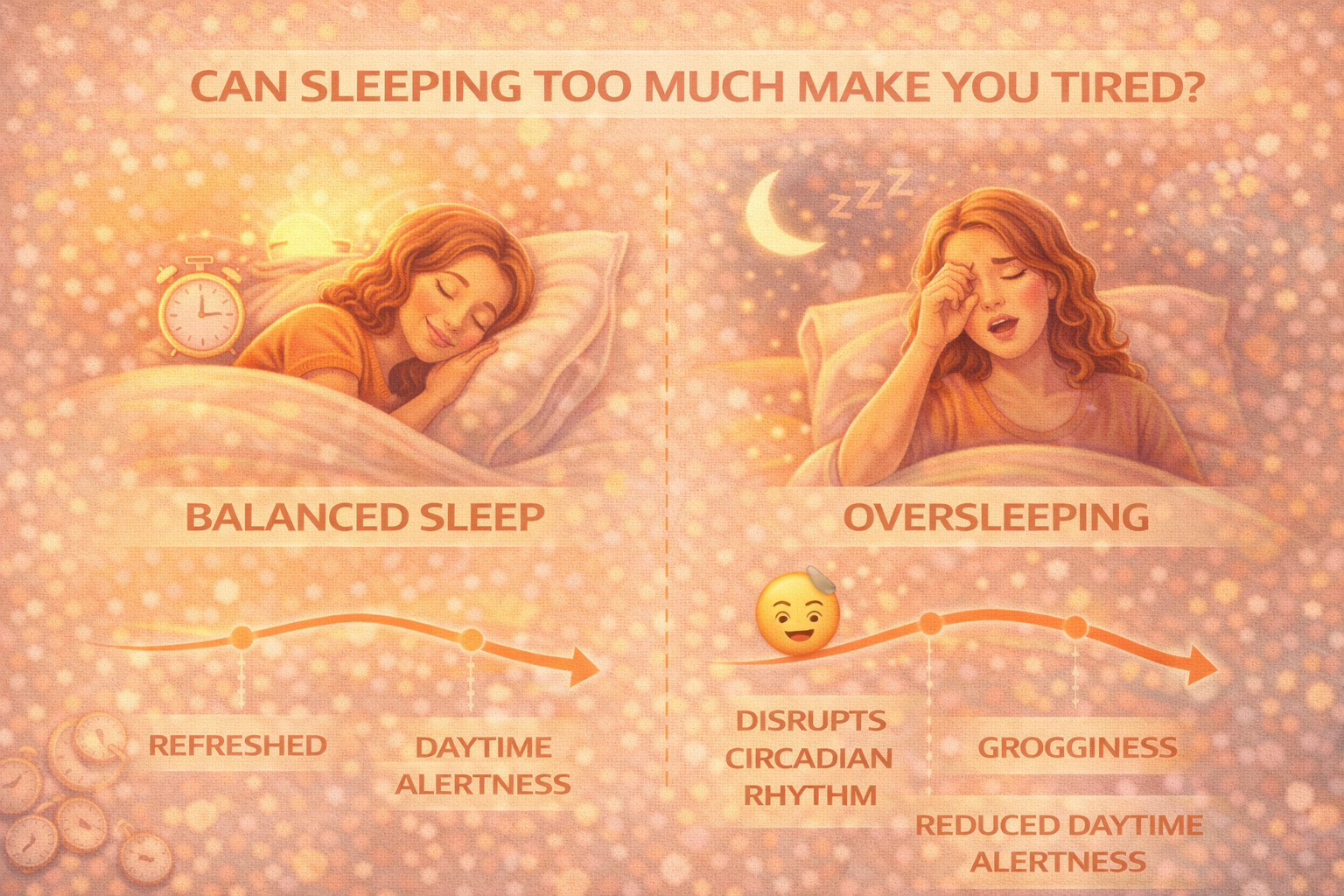

Circadian Rhythm and Oversleeping

The circadian rhythm determines when the brain is ready to wake up.

If you continue sleeping past this natural wake window, the brain begins shifting toward alertness even while you remain asleep. This creates internal conflict between sleep and wake systems.

As a result, waking up after oversleeping often feels sluggish and disorienting rather than refreshing.

Why Oversleeping Increases Sleep Inertia

Sleep inertia is the groggy, heavy feeling after waking.

Long sleep episodes increase the likelihood of waking from deep sleep stages. When this happens, the brain requires more time to fully transition into alertness.

Instead of easing the wake-up process, oversleeping can intensify inertia and reduce mental clarity.

Long Sleep Often Signals Poor Sleep Quality

Sleeping too much is frequently a response to inadequate recovery.

Fragmented sleep, reduced deep sleep, or circadian misalignment can leave the brain under-restored. In response, sleep pressure remains high, driving longer sleep durations without improving how rested you feel.

In these cases, long sleep is a symptom, not a solution.

Oversleeping and Circadian Drift

Regularly sleeping in can shift the circadian rhythm later.

This delay makes it harder to fall asleep the following night, creating a cycle of late bedtimes and late wake-ups. Over time, this pattern increases fatigue rather than resolving it.

What feels like recovery may quietly reinforce misalignment.

Mental and Emotional Effects of Excessive Sleep

Oversleeping affects more than physical energy.

It is often associated with:

-

reduced mental sharpness

-

lower motivation

-

emotional flatness

-

difficulty initiating tasks

These effects reflect circadian disruption and incomplete recovery rather than restfulness.

Why More Sleep Doesn’t Fix Chronic Fatigue

Chronic fatigue is rarely caused by insufficient sleep alone.

When fatigue results from stress, disrupted sleep architecture, or circadian instability, extending sleep duration does not address the underlying cause. The brain remains out of sync.

This is why some people feel better with slightly less but better-timed sleep.

When Longer Sleep Is Actually Appropriate

There are situations where longer sleep is necessary.

Acute sleep deprivation, illness, intense physical exertion, or recovery periods can legitimately increase sleep needs. In these contexts, longer sleep supports healing rather than undermines energy.

The key difference is whether longer sleep restores clarity or perpetuates fatigue.

Finding the Right Amount of Sleep

The optimal amount of sleep is individual and timing-dependent.

When sleep is well-aligned, duration often stabilizes naturally. The body wakes more easily, and energy feels more consistent throughout the day.

The goal is not maximizing hours in bed, but matching sleep duration to biological need and timing.

The Core Idea to Remember

Sleeping too much can make you feel tired when it disrupts circadian timing or reflects poor sleep quality.

Energy does not come from accumulating hours in bed. It comes from sleep that is efficient, well-timed, and biologically aligned.

When sleep timing is right, the brain takes what it needs — and more sleep stops being necessary.