How sleep improves thinking capacity, efficiency, and mental performance

Sleep is often treated as maintenance — something the brain needs to avoid malfunction. In reality, sleep does much more than preserve function. It actively upgrades how the brain operates.

After good sleep, thinking feels clearer, learning is faster, focus lasts longer, and mental effort decreases. These improvements are not psychological or motivational. They reflect measurable changes in how efficiently the brain processes information. Sleep does not just restore baseline performance — it enhances cognitive capability.

A Cognitive Upgrade, Not a Reset

A reset returns a system to its original state.

Sleep goes further. It reorganizes neural networks, improves signal efficiency, and optimizes how information flows across the brain. This is why performance after good sleep often exceeds performance before sleep.

The brain wakes up not just repaired, but refined.

How Sleep Improves Neural Efficiency

During sleep, the brain reduces unnecessary neural noise.

Connections that are weak or redundant are downregulated, while important pathways are strengthened. This increases signal-to-noise ratio, allowing thoughts to move more directly and with less effort.

Efficient brains think faster using less energy.

Deep Sleep and Core Cognitive Power

Deep sleep supports foundational cognitive strength.

During slow-wave sleep, large-scale brain synchronization improves communication between regions responsible for reasoning, working memory, and attention control. This synchronization reduces fragmentation in thinking.

When deep sleep is reduced, cognition becomes less stable and more effortful.

REM Sleep and Cognitive Integration

REM sleep drives integration across brain systems.

It allows distant concepts to connect, supporting creativity, insight, and flexible problem-solving. This integrative processing explains why solutions and ideas often emerge effortlessly after sleep.

REM sleep upgrades how knowledge is used, not just stored.

Why Sleep Makes Thinking Feel Easier

After good sleep, cognitive tasks feel lighter.

This is not because tasks are simpler, but because the brain processes them more efficiently. Less mental effort is required to maintain focus, reason through complexity, or make decisions.

Ease is a sign of efficiency, not laziness.

Sleep and Working Memory Capacity

Working memory is a bottleneck for thinking.

Sleep restores working memory capacity, allowing more information to be held and manipulated at once. This improves comprehension, multitasking, and problem-solving speed.

Poor sleep narrows this capacity, slowing cognition across the board.

Circadian Alignment and Cognitive Stability

Sleep timing affects cognitive upgrades.

When sleep aligns with circadian rhythm, alertness and performance remain stable throughout the day. Mistimed sleep produces uneven upgrades — moments of clarity followed by fog.

Biological timing determines how fully the upgrade applies.

Why Sleep Outperforms Effort

Effort cannot substitute for neural efficiency.

Trying harder while sleep-deprived increases cognitive strain without restoring capacity. The brain continues operating below optimal efficiency.

Sleep upgrades the system so effort becomes effective again.

Long-Term Cognitive Benefits of Sleep

Over time, consistent good sleep compounds benefits.

Learning accelerates, mental endurance increases, and cognitive resilience improves. These effects are cumulative and protective against long-term decline.

Sleep upgrades are not one-time events — they build.

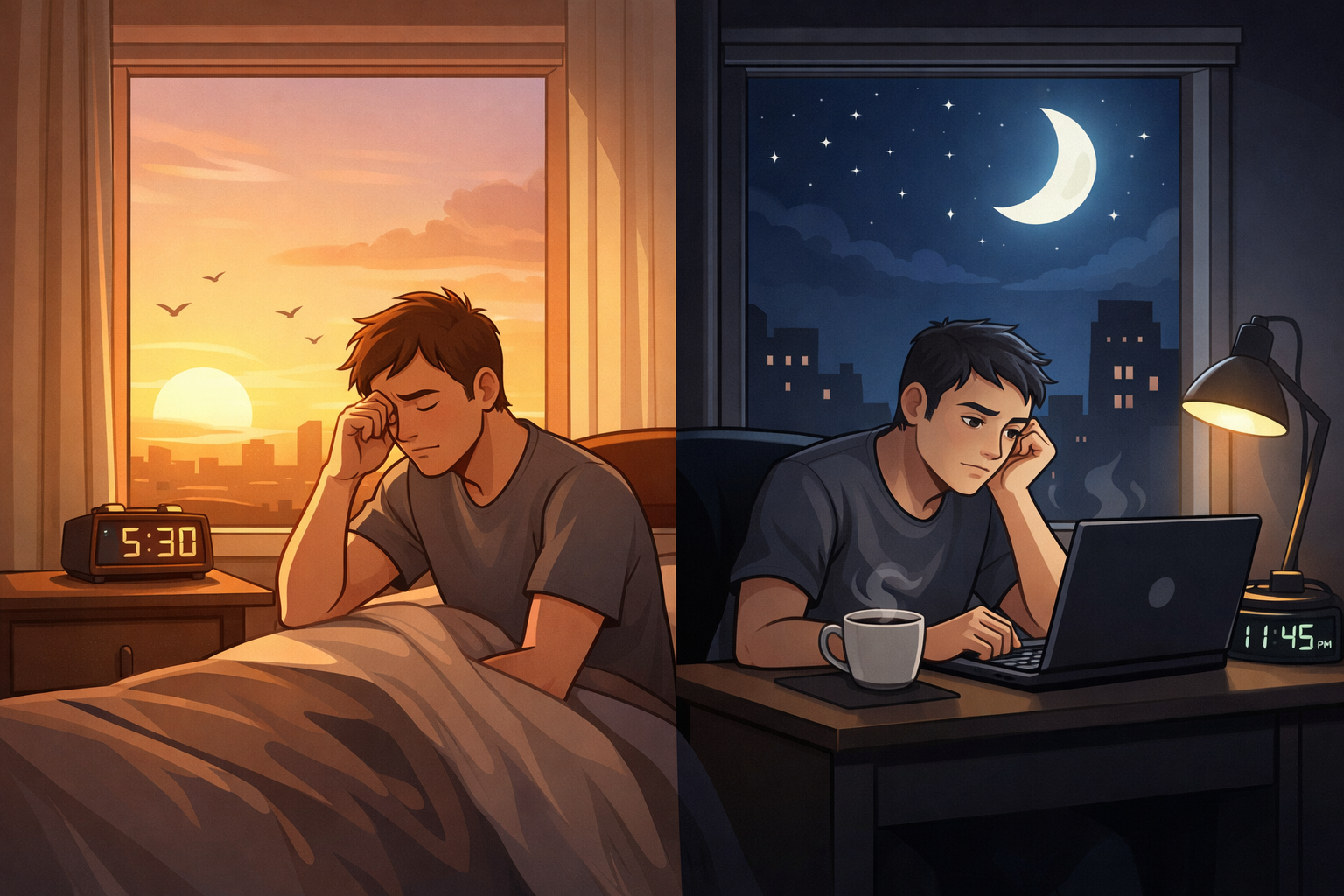

Why Poor Sleep Feels Like a Downgrade

When sleep is disrupted, the opposite occurs.

Neural noise increases, integration weakens, and efficiency drops. Thinking becomes slower, narrower, and more exhausting.

This is not loss of ability — it is loss of optimization.

The Core Idea to Remember

Sleep is a cognitive upgrade because it improves how the brain operates.

By increasing efficiency, integration, and capacity, sleep enhances thinking beyond baseline function. It does not add intelligence — it removes friction.

When sleep is protected, the brain doesn’t just recover.

It levels up.