Why nighttime light disrupts circadian signals and keeps the brain in daytime mode

The brain relies on light to understand time. When light appears at night, that understanding breaks down. Even when you feel tired, nighttime light sends a conflicting message: stay alert.

This confusion doesn’t just delay sleep. It disrupts circadian timing, weakens sleep depth, and interferes with emotional and cognitive recovery. Light at night tells the brain the wrong story about where it is in the day–night cycle.

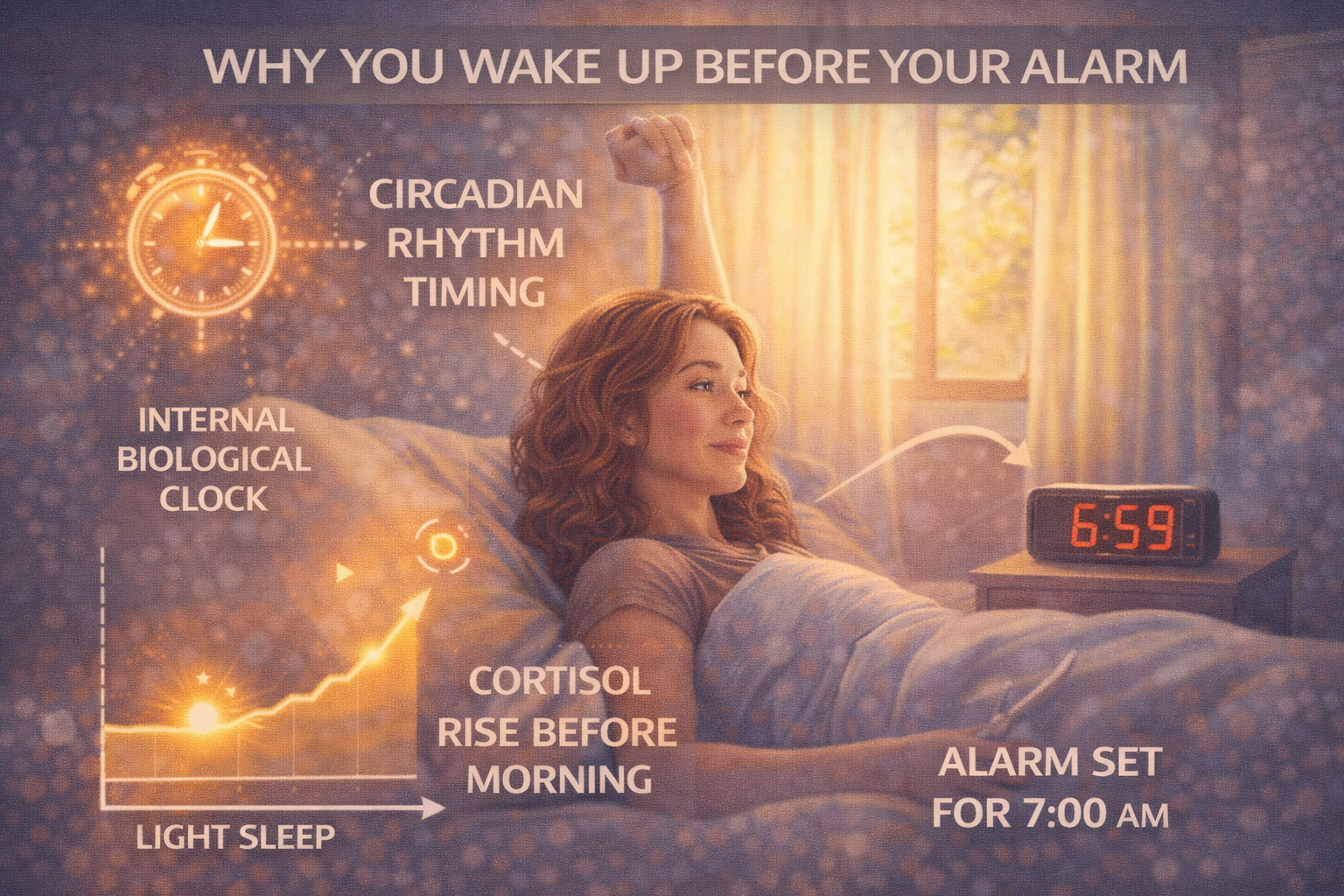

The Brain Uses Light to Tell Time

Timekeeping is biological.

Specialized light-sensitive cells in the eyes send continuous timing information to the brain’s internal clock. This clock uses light to coordinate sleep, hormones, alertness, and metabolism.

At night, the brain expects darkness. Light breaks that expectation.

Why Nighttime Light Sends Conflicting Signals

Light equals daytime to the brain.

When light is detected at night, the brain interprets it as extended day—even if the intensity is modest. This delays the transition into night mode and keeps alert systems active.

The result is biological confusion, not relaxation.

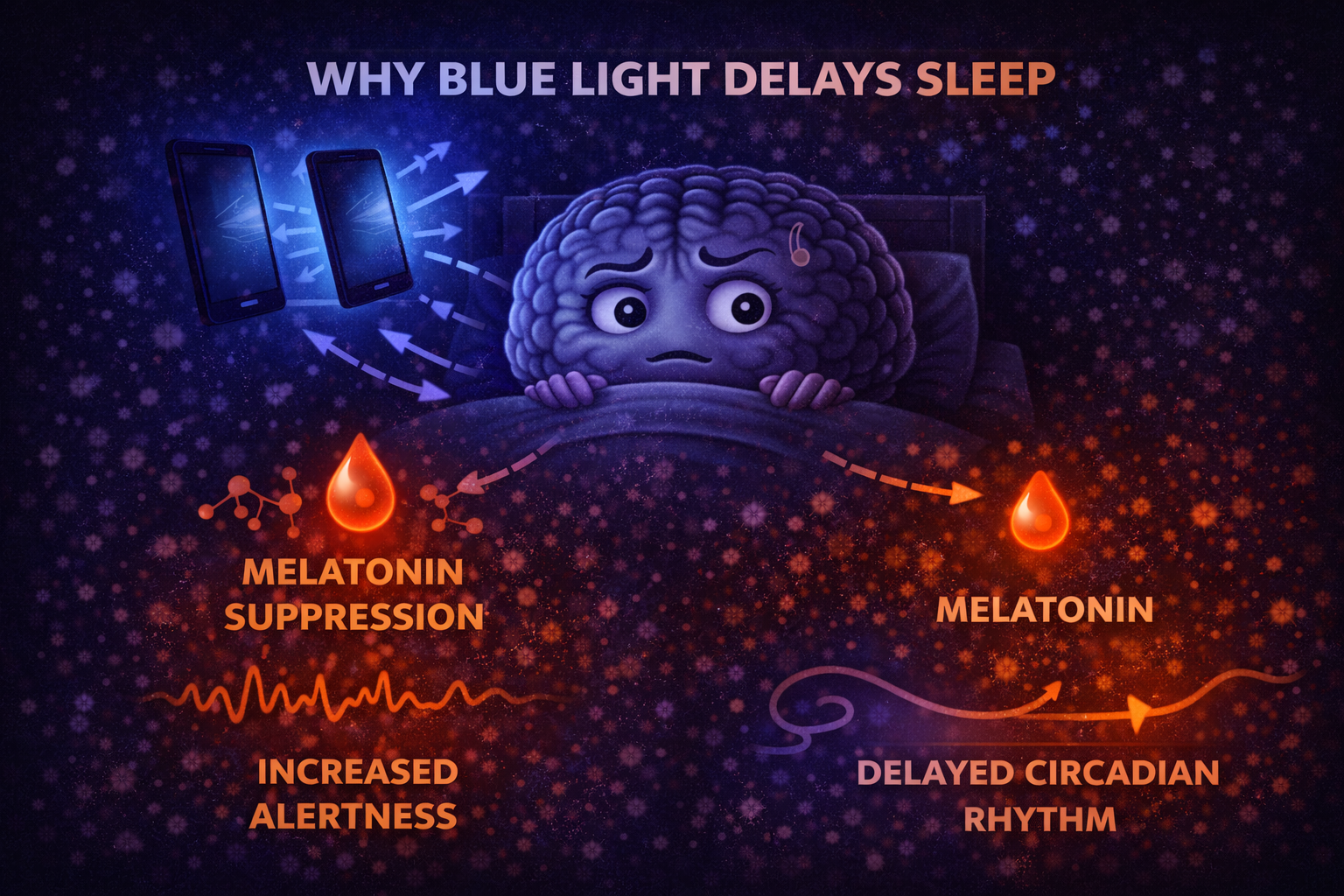

How Light at Night Suppresses Melatonin

Melatonin signals night.

In darkness, melatonin rises and coordinates nighttime physiology. Light exposure at night suppresses melatonin, delaying sleepiness and reducing sleep quality.

Even brief exposure can disrupt this signal.

Light at Night and Increased Alertness

Nighttime light actively stimulates the brain.

It increases reaction time, focus, and neural activity. This makes the brain feel “on” when it should be powering down.

Feeling tired does not override this signal.

Why the Brain Can’t Ignore Nighttime Light

The circadian system is automatic.

It does not respond to intention or habit. Light signals are processed reflexively, bypassing conscious control.

This is why “just relaxing” under bright light doesn’t prepare the brain for sleep.

Light at Night and Circadian Delay

Repeated nighttime light shifts the internal clock.

Sleepiness appears later, wake times drift, and circadian alignment weakens. Over time, this creates chronic misalignment between biological night and social schedules.

Sleep becomes inconsistent and fragmented.

How Nighttime Light Affects Sleep Depth

Confusion persists after sleep begins.

Light exposure at night reduces deep sleep and disrupts REM sleep by weakening circadian signaling. Sleep may be long but shallow.

Recovery processes remain incomplete.

Why Dim Light Still Matters

Low light is not neutral.

The circadian system is highly sensitive, especially in the evening and at night. Dim room lighting, screens, or ambient glow can still interfere with nighttime signaling.

Small signals add up biologically.

Light at Night and Emotional Regulation

Nighttime light affects more than sleep.

By disrupting sleep architecture, light at night increases emotional reactivity, stress sensitivity, and mood instability the next day.

The effects accumulate gradually.

Why Modern Environments Increase Confusion

Modern nights are rarely dark.

Streetlights, indoor lighting, devices, and illuminated screens keep light present far beyond sunset. The brain receives mixed signals every night.

This constant ambiguity prevents full nighttime shutdown.

Reducing Confusion Through Darkness

Clarity restores sleep biology.

Reducing light exposure at night allows the brain to recognize night properly. Melatonin rises, alert systems quiet down, and sleep deepens naturally.

Darkness resolves confusion.

Why Nighttime Darkness Improves Sleep Without Effort

When signals are clear, sleep follows.

The brain doesn’t need to be forced into rest—it needs accurate information. Darkness provides that information.

Sleep improves when the brain understands that night has truly arrived.

The Core Idea to Remember

Light at night confuses the brain because it sends a daytime signal during biological night.

By suppressing melatonin, increasing alertness, and delaying circadian timing, nighttime light keeps the brain partially awake even when tired.

Sleep improves when nighttime light is reduced and darkness is allowed to do its job.